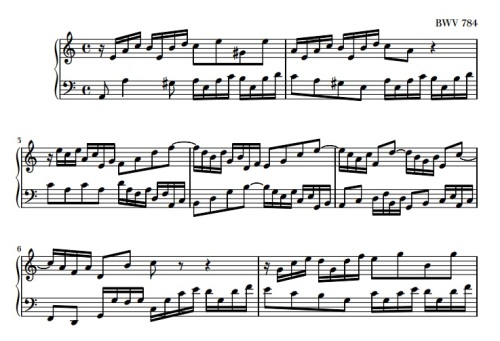

Earlier this term I began teaching Bach’s Invention in a minor, BWV 784 to one of my piano pupils. This is the beginning of her second term of lessons with me, and although she is a bright and diligent pupil, her tendency when learning a new piece is still simply to begin at the beginning and do her best to play the notes. The analogy which I often use is that of an intrepid explorer hacking her way through the dense jungle armed only with a machete – she’ll get there in the end – wherever there is – but it’s not going to be pretty! And when she does arrive at her destination, she’ll probably have little or no recollection of any detail of the journey along the way.

We can do better than that. Bach wrote these pieces to teach his pupils not only how to play, but also how music is put together. Why should we not do the same?

First of all, what key is it in? Pupil, being on the ball, answers A minor.

How does she know? There is no key signature, and there are G#s – which are the raised 7th. Good knowledge. [And how do I know it’s in A minor? From the title at the top of the page – “Invention in A minor”!]

And what is the other chord which Bach is most likely going to use? The dominant.

Excellent answer, and what is the dominant in this key? E. Finish your sentence…. E major. Good, the dominant in a minor key is major, because of the raised 7th.

Now, can you play me an arpeggio of A minor, just an octave up and down? Here’s the pulse. Of course she can. And now four whole beats worth, in quavers, but now you can change direction whenever you like. [Quick demonstration, with the pulse still going]. Again, it’s a straightforward task for her. And now the same, but this time let’s include some passing notes so that we have a mix of steps and thirds. No problem.

We quickly do the same in the dominant, and before long we are changing fluently between tonic and dominant every four beats, complete with a single bass note per bar in the left hand.

Now, and only now, do we look at the music in detail for the first time. Machete-style, she would have hacked away, one unrelated note at a time – such an unrewarding and largely meaningless task. But now she can see the arpeggio shapes instantly, and realises that the notes which aren’t in the arpeggio must be passing notes. So they make sense too. We notice that the E major arpeggios are actually dominant sevenths.

Going onto the second line (still playing RH only) she is quick to notice that everything is made of arpeggio shapes. How often does the chord change? Twice every bar. And then she notices that there is a sequence; her ears are also helping to guide her along what is looking more and more like a clear path, even though she has never been down it before. Observe, the circle of fifths in action rather than just presented as cold, dry theory – at last, we have found a use for it!

Now she plays through the left hand, and quickly notices that it is copying the right hand – imitation. And half way through bar 6, having noticed the same melodic shape but now starting on a different note, she observes that we have modulated – to C major. How’s that related? It’s the relative major.

This has probably taken about 10 to 15 minutes, but she now has a really good idea of the lie of the land of the whole piece. Initially it looked like a jungle, with huge areas of impenetrable semiquavers, but now that she can see the harmonic outline (and knows what to listen for) the way forward is just so much clearer. It is so much easier to learn when we understand how the music is put together.

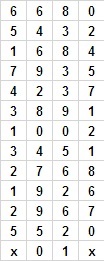

In the 1920s, the Russian neuropsycologist Alexander Luria began a series of experiments on Solomon Shereshevsky, who had a seemingly endless memory. Once he had studied a chart like the one here for about 3 minutes, he could recall it – reading up, down, backwards – not just for a few days, but for years! Shereshevsky was a synesthete, and for him numbers, letters and words were tinted with associations of colour, taste, shape etc which enhanced his recall. He might have had an amazing memory, but because his ‘memory filters’ were effectively switched off, he found day to day life very difficult because he found it impossible to sift out the constant conflict of associations attached to just about everything.

In the 1920s, the Russian neuropsycologist Alexander Luria began a series of experiments on Solomon Shereshevsky, who had a seemingly endless memory. Once he had studied a chart like the one here for about 3 minutes, he could recall it – reading up, down, backwards – not just for a few days, but for years! Shereshevsky was a synesthete, and for him numbers, letters and words were tinted with associations of colour, taste, shape etc which enhanced his recall. He might have had an amazing memory, but because his ‘memory filters’ were effectively switched off, he found day to day life very difficult because he found it impossible to sift out the constant conflict of associations attached to just about everything.

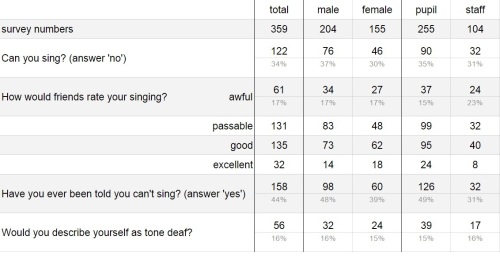

The benefits of singing in a choir are well documented. In the case of the ‘Choir who can’t sing’ my hope is that both the boys themselves, and those who hear them, accept that anyone can sing. I think it’s a strong message. My long-dreamed-of day when the whole school comes to Chapel and sings has arrived, and last Saturday the school sang Be thou my vision and In Christ alone with extraordinary energy. The choir has been part of changing the whole school attitude towards singing, and I believe that the school is much healthier for it.

The benefits of singing in a choir are well documented. In the case of the ‘Choir who can’t sing’ my hope is that both the boys themselves, and those who hear them, accept that anyone can sing. I think it’s a strong message. My long-dreamed-of day when the whole school comes to Chapel and sings has arrived, and last Saturday the school sang Be thou my vision and In Christ alone with extraordinary energy. The choir has been part of changing the whole school attitude towards singing, and I believe that the school is much healthier for it. So, back to my piano pupil. I could instruct her, in great detail, to play each bar in a particular way – begin quietly, crescendo here etc – but who am I kidding? I know that this isn’t the way to draw out her musicianship. Worse, sadly, she might not know that; she could end up giving a very ‘musical’ performance and not have the first idea why – she’s just following my instructions. That would not be empowering teaching.

So, back to my piano pupil. I could instruct her, in great detail, to play each bar in a particular way – begin quietly, crescendo here etc – but who am I kidding? I know that this isn’t the way to draw out her musicianship. Worse, sadly, she might not know that; she could end up giving a very ‘musical’ performance and not have the first idea why – she’s just following my instructions. That would not be empowering teaching.

My point is this – why is the pupil calling

My point is this – why is the pupil calling