How would you fancy a new ‘processor’? An instant upgrade, which gives you the ability to read music at x3, x5 or even x10 your previous capacity. Sounds good eh?

I had a wonderful break-through with a piano pupil towards the end of last term. He is a fine musician and clearly loves playing the piano, but he is also a classic example of a student who enjoys playing, but not so much the work involved in getting there!

He is very bright and is not afraid to read, and perhaps surprisingly, therein lies one of his weaknesses; he reads everything, all of the time, until such point as the music is ‘in the system’ and muscle memory has taken over. In itself the reading part is fine, but it’s hard work on the brain, reading all that data all of the time, and this is the part which he doesn’t enjoy. My teaching focus with him has always been to find ways to engage his intellect, so that the practice process itself becomes interesting and challenging to him, rather than just a chore to be accomplished. To quote Daniel Pink (Drive, 2009) “The joy is in the pursuit more than the realisation. In the end, mastery attracts precisely because mastery eludes.”

So how about that upgrade then?

We have been working on the final movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in E major, op.14/1. Having asked him to prepare a section of the movement, I was disappointed to find that he had come back, as ever, able to play the notes, but not really having learned them; and not just that, but complaining that he just couldn’t get excited about having to learn all those notes. I’m not surprised – once the cognitive strain sets in (and it doesn’t take long) it’s not much fun.

So how about using another resource in addition to reading; memory perhaps? Bar 58 is in b minor, and it really is just arpeggios. Let’s look at the detail: the first falling arpeggio shape starts on F#, and then it’s just three more falling arpeggio groups, all starting on B but an octave lower each time. The final one rises again. There are 25 notes in these two bars, 25 bits of data. But we can reduce that to 5, at most.

Bars (60-61). The bass falls by a step (and indeed that pattern continues through to bar 66). What kind of chord is this? A dominant seventh on D – but note that the fifth (A) is missing. Apart from that, it’s the very same shape as bars 58-59, and even starts on the same note, F#. Nice pattern 🙂

And then bars 62-63. G major [perhaps not surprising following the D7 chord.] The same shape as before, so all we need to remember is that the RH starts on a G. Bearing in mind that everything else is the same as bars 58-59, I’d go so far as to suggest that these 25 notes can be reduced to ONE detail only; the RH starts on a G. Bars 64-65 is another dominant seventh, as before with the fifth (F#) missing.

These eight bars have now become an intriguing memory game. There may be a little bit of thinking still to do, but nothing like the cognitive strain required to read all of those notes at speed; in fact, we’ve opened up an entirely new set of skills. No reading needed at all, which incidentally frees up the eyes to see some of those patterns which we’ve found. The joy is, it has taken him all of about 5 minutes to take all of this in, it’s engaged him fully, and the work is done! And now he’s keen to continue into the next passage and apply the same method.

footnote

The key here is in actively looking for patterns, and without a working knowledge of theory a student is never going to unlock this upgrade. ABRSM may have dumbed down their grade 5 theory exam of late, but the requirement to pass it in order to progress onto the higher practical grades remains very sensible. Teaching theory needs to be an integral part of every instrumental lesson.

*footnote to footnote

Over the past few weeks the change in this student’s learning is so evident. He has moved from reading to actively seeking patterns, and he is now using his memory as an active strategy rather than it just being a passive by-product. Upgrade most definitely achieved!

Perhaps the doors open, and the bonnet? But if you open them too far, they snap off and then you can’t put them back on again! Maybe the plastic seats inside rattle a bit if you shake it. If you’re really lucky, the tyres are rubber rather than plastic, and you can take them off and chew them! And if you break the wheels, the metal axles can bend, and they’re sharp too. The paintwork chips if you drop it lots, and you can make all sorts of exciting dents in the dining room table if you bang it hard enough.

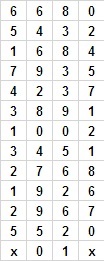

Perhaps the doors open, and the bonnet? But if you open them too far, they snap off and then you can’t put them back on again! Maybe the plastic seats inside rattle a bit if you shake it. If you’re really lucky, the tyres are rubber rather than plastic, and you can take them off and chew them! And if you break the wheels, the metal axles can bend, and they’re sharp too. The paintwork chips if you drop it lots, and you can make all sorts of exciting dents in the dining room table if you bang it hard enough. In the 1920s, the Russian neuropsycologist Alexander Luria began a series of experiments on Solomon Shereshevsky, who had a seemingly endless memory. Once he had studied a chart like the one here for about 3 minutes, he could recall it – reading up, down, backwards – not just for a few days, but for years! Shereshevsky was a synesthete, and for him numbers, letters and words were tinted with associations of colour, taste, shape etc which enhanced his recall. He might have had an amazing memory, but because his ‘memory filters’ were effectively switched off, he found day to day life very difficult because he found it impossible to sift out the constant conflict of associations attached to just about everything.

In the 1920s, the Russian neuropsycologist Alexander Luria began a series of experiments on Solomon Shereshevsky, who had a seemingly endless memory. Once he had studied a chart like the one here for about 3 minutes, he could recall it – reading up, down, backwards – not just for a few days, but for years! Shereshevsky was a synesthete, and for him numbers, letters and words were tinted with associations of colour, taste, shape etc which enhanced his recall. He might have had an amazing memory, but because his ‘memory filters’ were effectively switched off, he found day to day life very difficult because he found it impossible to sift out the constant conflict of associations attached to just about everything.

So, back to my piano pupil. I could instruct her, in great detail, to play each bar in a particular way – begin quietly, crescendo here etc – but who am I kidding? I know that this isn’t the way to draw out her musicianship. Worse, sadly, she might not know that; she could end up giving a very ‘musical’ performance and not have the first idea why – she’s just following my instructions. That would not be empowering teaching.

So, back to my piano pupil. I could instruct her, in great detail, to play each bar in a particular way – begin quietly, crescendo here etc – but who am I kidding? I know that this isn’t the way to draw out her musicianship. Worse, sadly, she might not know that; she could end up giving a very ‘musical’ performance and not have the first idea why – she’s just following my instructions. That would not be empowering teaching.