In January I stated my intention (see Fantasy Piano Recital) to prepare for an ABRSM diploma, and the five months since then has been the most amazing journey of discovery for me. Not all of it good, it has to be said, but a learning experience which has been hugely worthwhile. Some random observations…

My family have more or less banned me from practising at home, and my 11 year old son can sing my entire 35 minute recital note-perfect from beginning to end! I have always loved practising, and it is fair to say that this project has brought out some of my more obsessional qualities! However, I don’t think it’s all bad news; as a father, I guess I have been modelling commitment and perseverance to my four sons, and indeed in the last week my eldest (aged 17) has decided that he wants to apply to the Royal College of Music next year! And so the cycle continues….!

Apart from the Stravinsky, which I wrestled with largely unsuccessfully as a teenager, all of this repertoire was new to me in January, and I set out with the intention of integrating the memory aspect from the very beginning. In other words, rather than learning the notes and then working out how to memorise them, I deliberately set out to commit short passages to memory from the outset. The result has been that over the past few months I have spent more and more time practising with no music in front of me at all, to the extent that it has become entirely normal not to have it there.

Some parts of the repertoire have been much more difficult to memorise than others. The Schubert, for instance, is physically very ‘samey’ throughout, and the obscure key does not help – looking down, my eyes say B major, but the score says C flat major! And in the slow movement of the Beethoven it has been equally difficult to remember the subtle differences between very similar sections. On the other hand, some of the more technical passages (sequences in Bach and scales and arpeggios in Beethoven and Fauré) have been surprisingly easy to memorise, especially once the basic harmonic plan of the section has been established. The Stravinsky is so physical that actually the muscle memory seems to remain the most reliable method.

Whatever the methods, over the course of the past few weeks the entire programme has fallen into place, in as much as I have been able to play from beginning to end with increasing confidence, and certainly with no need to look at the scores. If anything, I have needed to make a concerted effort to open the music to check details of dynamics and phrasing as it has been months now since I have even looked at the dots!

The freedom gained has been truly wonderful. I have spent a great deal of time with a rather wonderful Steinway grand piano, and whereas in the past I have been content to sit at a closed piano and play the notes in front of me, I now open the lid and even remove the music desk so that I can hear the instrument more clearly; I listen more carefully. And now that the eyes are free, there are so many things to look at, to concentrate on. Fingers, fingers reflected in the fallboard, hammers hitting the strings, beautiful aesthetics of a fine concert hall, or nothing at all – eyes closed. I’ve experimented with them all, and the different focus which each one brings has been such an enjoyable experience.

Being without music has certainly sharpened my senses. Physically, I am now much more at liberty to see what I am doing with my fingers; watching the weight of the right hand little finger in the Schubert Impromptu makes such a difference to my focus. But this in nothing compared with how much the ear is switched on to sound!

So with less than a month to go, I took the plunge on Tuesday evening and performed to a real audience, my first solo piano recital in 26 years! I am an extremely experienced performer as organist, piano accompanist and conductor, but the single element under scrutiny here was whether my memory could cope with the additional strain of nerves. Getting fired up and excited about playing in a match can be hugely beneficial, but it is perhaps less helpful when you need to retain a vast amount of highly refined detail for a sustained period! The outcome – I really didn’t enjoy one moment of it, since I spent the whole time thinking “Don’t forget it, you’re going to forget it” and barely any making music. A schoolboy error? Yes!!

Not all is lost though, quite the opposite in fact. I think it was a necessary experience, and apart from anything else it has realigned my focus significantly. For although my own self-imposed target (not required for the exam) is to play from memory, the exam itself is neither a piano diploma nor a memory diploma – it is a performance diploma. Time to stop stressing about the memory and move on and up to the next level.

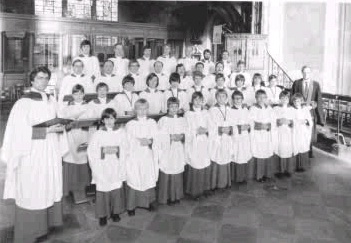

The other outcome is that this was a brilliant learning experience, not only for me but also for my willing audience, made up for members of the choral society and a few school colleagues and pupils. As a teacher, I think it is vitally important that they should see that I am still learning, and moreover that I am not afraid to show them that learning is not always easy. As ever, although the exam day looms larger and I want to do the very best that I can on the day, the process has been transformational, and will bear fruit long after the outcome (pass or fail?!) has faded.