You would imagine that having a piano pupil who can sight-read well makes teaching them a real joy. Well, yes it does in some ways, but in others it can be quite challenging. Here is Plato on the subject:

If men learn to write, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls; they will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks.

As our pupils progress, it’s a fact that some of the learning methods which they have used very successfully in the past can cease to be as effective as they once were. However good their reading is, there comes a point when it’s not enough, and we need to bring other things into play as well.

I posted an article recently on teaching a Bach Two-part Invention. Despite my pupil being quick to see how the music is put together, the reality is that playing a piece like this hands together presents some very real problems. Looking at the music vertically, there is a lot of information to take in, and I mean a lot. Too much even. The solution? Don’t read.

Since the advent of FMRI scanning scientists have been able to observe brain activity in considerable detail. Interestingly, if you monitor the areas of the brain which are in use when a musician plays his instrument, the scans look almost identical to those done when the same musician imagines playing their instrument. Wow! I believe that this little bit of information adds weight to how I would approach putting the A minor Invention hands together.

Since the advent of FMRI scanning scientists have been able to observe brain activity in considerable detail. Interestingly, if you monitor the areas of the brain which are in use when a musician plays his instrument, the scans look almost identical to those done when the same musician imagines playing their instrument. Wow! I believe that this little bit of information adds weight to how I would approach putting the A minor Invention hands together.

In short, play the right hand and sing the left hand! Singing badly is fine – just the rhythm and the general melodic shape. It’s an engaging task for the pupil, and although it is easier than diving in hands together, it is by no means straightforward. But once they can perform a few bars or so in this way [and the other way up too] the benefits are clear: the left hand part is being run from a different system – not just reading, but something internal (or to go back to Plato, something “from within themselves.” And now, when we play the left hand, it is not just reading which is going on – it’s running directly from something internal as well, reducing the cognitive strain which would be present from reading two lines simultaneously.

The ideal is that eventually everything is internalised, and that reference to the dots on the page becomes less and less necessary. So why is that so many of our pupils still have the notes on the stand weeks or even months into learning a piece of music? Teaching in this way develops so many aspects of musicianship – co-ordination, aural skills, memory, inner hearing, the lot – and it’s so important that we are doing all that we can to empower our pupils to think for themselves. And, ironically, it also improves their sight-reading!

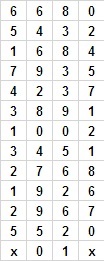

In the 1920s, the Russian neuropsycologist Alexander Luria began a series of experiments on Solomon Shereshevsky, who had a seemingly endless memory. Once he had studied a chart like the one here for about 3 minutes, he could recall it – reading up, down, backwards – not just for a few days, but for years! Shereshevsky was a synesthete, and for him numbers, letters and words were tinted with associations of colour, taste, shape etc which enhanced his recall. He might have had an amazing memory, but because his ‘memory filters’ were effectively switched off, he found day to day life very difficult because he found it impossible to sift out the constant conflict of associations attached to just about everything.

In the 1920s, the Russian neuropsycologist Alexander Luria began a series of experiments on Solomon Shereshevsky, who had a seemingly endless memory. Once he had studied a chart like the one here for about 3 minutes, he could recall it – reading up, down, backwards – not just for a few days, but for years! Shereshevsky was a synesthete, and for him numbers, letters and words were tinted with associations of colour, taste, shape etc which enhanced his recall. He might have had an amazing memory, but because his ‘memory filters’ were effectively switched off, he found day to day life very difficult because he found it impossible to sift out the constant conflict of associations attached to just about everything.