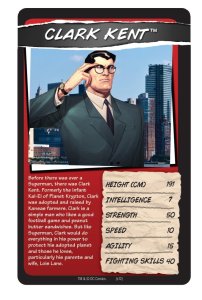

The word performance, to me at least, means putting on a show. In theatrical terms, it’s an event which happens on stage, under lights, to entertain, to impress, to enthral.

What we don’t want the audience to see is all of the stuff behind the scenes: the heavily-annotated script dropped moments before in the wings, the director barking instructions into headsets: “20 seconds until scene change!” And we most definitely don’t want to know the human story behind how we have arrived at this point – the hours of learning, perhaps tears, the moment we nearly decided to throw in the towel altogether. No, a performance is exactly that – a show, a charade even, where we disclose only that which we want the audience to see and hear.

As a career schoolmaster I have spent countless hours in the exam room accompanying young musicians in every imaginable scenario from ropey grade 1 violin to effortless grade 8 French horn. Despite always having sought at the very least a quick run-through beforehand, there have of course been plenty of candidates whose counting (or lack of counting) has let them down, at which point it falls to me to stick with them and do my best to cover up any bumpy moments. We are, after all, giving a performance, and we don’t want our audience (in this instance the examiner) noticing anything untoward if we can help it! Not to discredit any examiners, but I don’t think anyone will disagree that a decent accompanist can add a little performance glitter and might occasionally be able to deceive their audience to the benefit of the exam candidate. It’s a performance, that’s what we do. We only show the stuff we want our audience to see.

The trouble with performance exams is that education is about teaching children how to do things which they can’t already do. In other words, we need to be able to see, to talk about, to examine the things which we can’t see. All of that back-stage stuff – the paint pots, the broken props, the tears, the tantrums – that is education happening right there. That’s the bit we need to be focusing on. If you only get to see the actual performance, you are just the audience. You have no idea about the performer and how they reached this point because the performer’s very purpose is to disguise this information from you. You have played no part in their ‘education’. You can only judge what you see and hear – it was a show.

The UK exam boards will defend their position until hell freezes over, telling you that they’re examining a different set of skills. ‘Communication, interpretation and delivery, musical continuity, stage presence…’ This generates so many questions in my mind, but the ones at the top of the list are:

If you’re looking for ‘communication, interpretation and delivery’ now, what on earth have you been looking for in the three pieces in all the exams held since 1880 (give or take a few years.) It actual defies belief that we are expected to fall for this…

Stage presence, in a video exam? You must surely be joking. Quick rewind to the first paragraph, teacher standing ‘in the wings’ just out of shot gesturing wildly to the candidate to *smile/relax/stop crying, it’s only the fifteenth take and if you get this one right we’ll call it a day (*delete as appropriate)

This leads to another question: has anyone else wondered why the ‘performance’ exam is not available as a face-to-face option? I’m serious, ask yourself the question, and then ask yourself whether you think this format is in the best interests of our young musicians and their musical education, or just suits the convenience of the exam board. Or whether it just hasn’t occurred to them yet, post-COVID, to offer this format face-to-face? Of course, in the case of at least one of the UK exam boards, all but one of their diplomas are now available only in recorded format. Incredible, you can attain a Fellowship diploma, in performance, without ever having performed live to a single person. The Emperor’s New Clothes indeed!

But my main questions are these. In the context of an exam board offering a performance exam, what exactly have you done to encourage the education of this child? What have you done to support the huge number of teachers in this country and beyond who look to you to give them a lead and help them to do the best job that they can? The short answer is that you haven’t: you just arranged the performance and now you’re sitting in the audience.

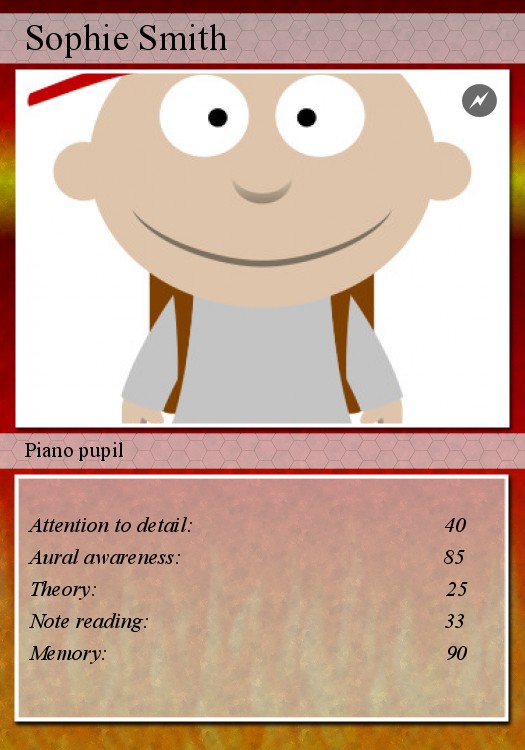

From an educational perspective, these ‘performance’ exams do little to support our young musicians and their teachers. In fact, they are doing the opposite – yes, dumbing down – by pretending that the performance is the main event, when actually it is the teaching which is where the focus needs to be. And yes, they will feed you the usual line about teachers having the freedom to teach all of the other things in their lessons – you know, the important stuff like literacy, musicianship, those things. But here’s the thing: they don’t. These examining bodies, whilst claiming to support the musical education of our children, are shouting loudly about an assessment system which is focused entirely on the performance, the show, the façade. They call it ‘playing to the candidates’ strengths’. I call it ignoring their education. Worse, they’re pretending that this is their education.

These UK exam boards have rightfully earned huge respect in their field over the course of the last hundred years and more, but with that comes responsibility. Their introduction of ‘performance’ grades, to the detriment of the actual education bit, sends a very loud signal to teachers, parents and pupils alike, many of whom still believe that what they are selling is of value. It says ‘take the easy route’. They want to have their cake and eat it; they’ll tell you that teachers are still at liberty to teach sight-reading etc, but then they flood the market with a product which undermines any credibility for an organisation which claims to support the learning of our young musicians.

From the outset, my wife and I have always spoken to our children in full sentences. So for instance, at meal times “Would you like a banana for pudding, or shall I see whether we have some yoghurts in the fridge?” A baby is not going to pick up all of the nuances in this sentence, but they know the

From the outset, my wife and I have always spoken to our children in full sentences. So for instance, at meal times “Would you like a banana for pudding, or shall I see whether we have some yoghurts in the fridge?” A baby is not going to pick up all of the nuances in this sentence, but they know the  Since the advent of

Since the advent of

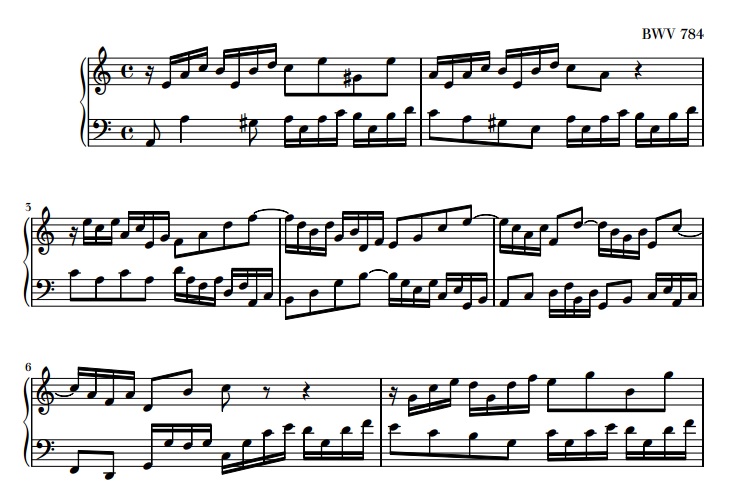

So, back to my piano pupil. I could instruct her, in great detail, to play each bar in a particular way – begin quietly, crescendo here etc – but who am I kidding? I know that this isn’t the way to draw out her musicianship. Worse, sadly, she might not know that; she could end up giving a very ‘musical’ performance and not have the first idea why – she’s just following my instructions. That would not be empowering teaching.

So, back to my piano pupil. I could instruct her, in great detail, to play each bar in a particular way – begin quietly, crescendo here etc – but who am I kidding? I know that this isn’t the way to draw out her musicianship. Worse, sadly, she might not know that; she could end up giving a very ‘musical’ performance and not have the first idea why – she’s just following my instructions. That would not be empowering teaching.

My point is this – why is the pupil calling

My point is this – why is the pupil calling

But for a sight-reading test, we need a different approach. Don’t correct the mistakes! In fact, it’s not unlike running a hurdles race (although I need to stress that I speak with very little first hand experience!) In the hurdles the athletes quite often hit the barriers – sometimes they wobble, sometimes they fall over (the hurdles that is, hopefully not the athletes!) but what they never do is go back and have another go. They just keep going, sometimes leaving a trail of destruction behind them. It doesn’t matter – once the barrier has been hit, it’s too late to do anything about it, so they just keep running to the finish line. In some ways, it’s quite satisfying to make mistakes and then to almost literally run away from them!

But for a sight-reading test, we need a different approach. Don’t correct the mistakes! In fact, it’s not unlike running a hurdles race (although I need to stress that I speak with very little first hand experience!) In the hurdles the athletes quite often hit the barriers – sometimes they wobble, sometimes they fall over (the hurdles that is, hopefully not the athletes!) but what they never do is go back and have another go. They just keep going, sometimes leaving a trail of destruction behind them. It doesn’t matter – once the barrier has been hit, it’s too late to do anything about it, so they just keep running to the finish line. In some ways, it’s quite satisfying to make mistakes and then to almost literally run away from them!